I read The Wicked + The Divine during its single issue run. It was a regular read and one of those books I anticipated arriving. It was not, however, my ur Gillean and McKelvie work. That would be Phonogram -- an indie comic with literary aspirations where young adults channel an unhealthy love of clubbing and pop music into literal "impact the physical world" magic. All this while the world is forcing them to reckon with the fact they have neither burned out nor faded away. Phonogram hit me at exactly the right time -- 2008, my peak clubbing years, and in what none of us fully realized were the final years of bohemian Portland.

The Wicked + The Divine was Gillean and McKelvie returning to indie work after a successful stint in the superhero factory and, in some ways, is each of them at the height of their powers (for a certain definition of powers). Its run date, from June 2014 to September 2019, are also some of the numbest years of my life. Between 2010 and 2013 I had started to pull back from club life and house parties, began to take work a bit more seriously, and traded those weekends out as "Alana Ash, lady of science" for drinking. Mostly alone. Alcoholism is a funny word, but it's one that fits.

By 2014 I realized I had a problem and started counting my drinks. In 2015 I was slightly horrified to find myself at 40 trying to live the life of a 32-year-old. The bins of clothes in my basement still tugged at me, but I couldn't see a path forward there. Instead, I did the other thing: Settled on a romantic relationship despite the red flags, took the regular corporate tech job, and started planning to turn 67.

All this was playing out as I read through "WicDiv" each month. I expected a re-read was going to be a feelings minefield and I wasn't wrong.

Mirrors

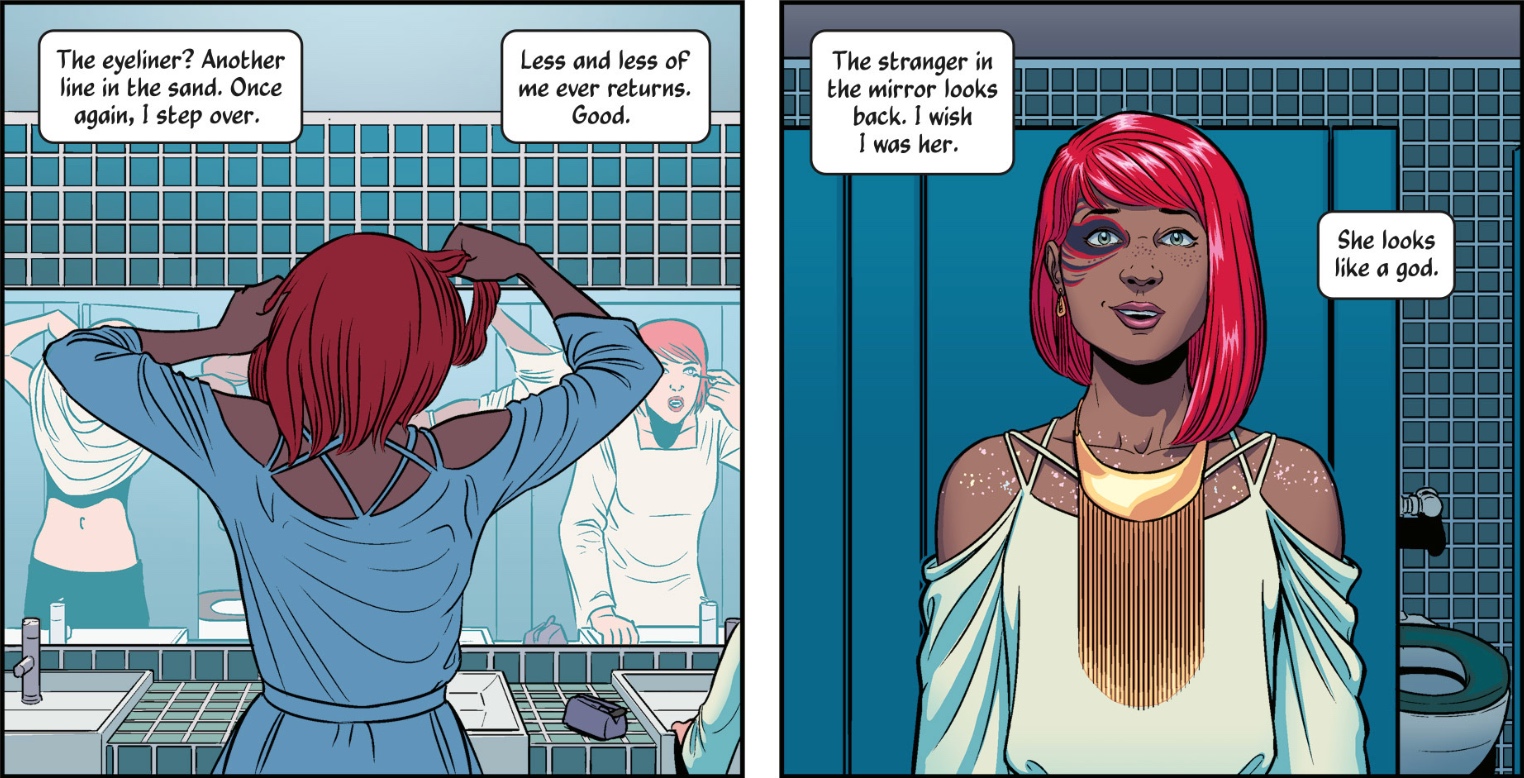

It only took 10 pages to be immediately hit in the gut by a scene. Here we see the book's primary protagonist, Laura Wilson, facing herself down in the mirror cosplaying one of the book's pop star gods.

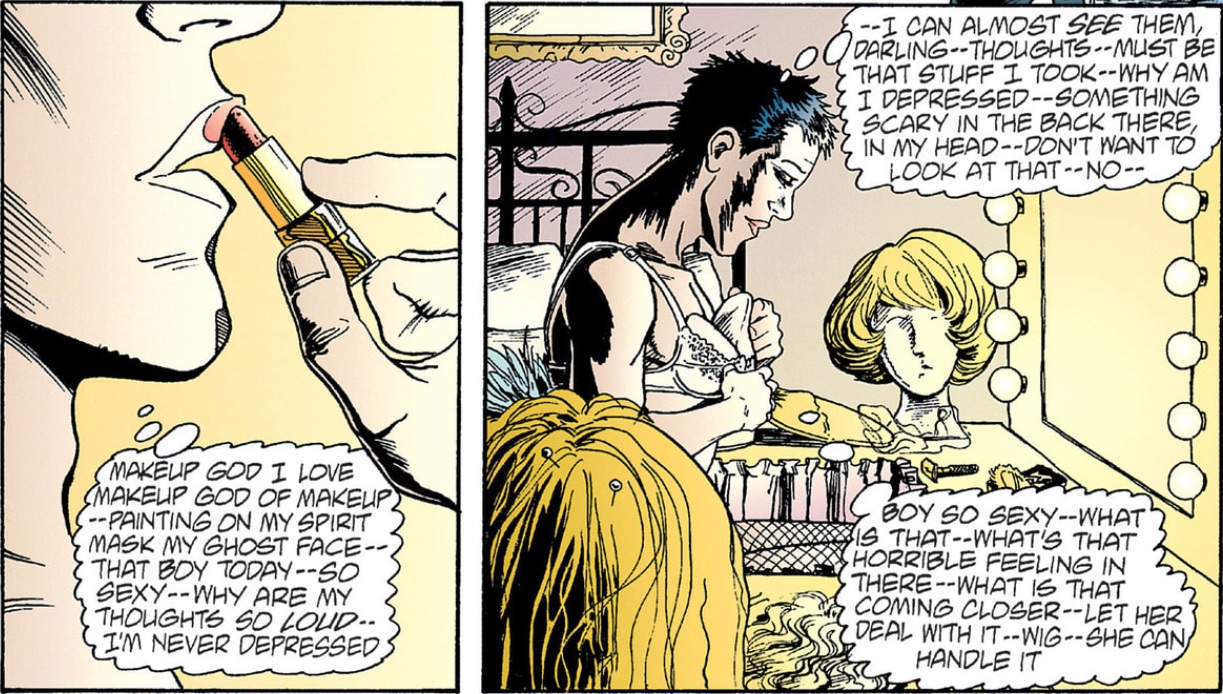

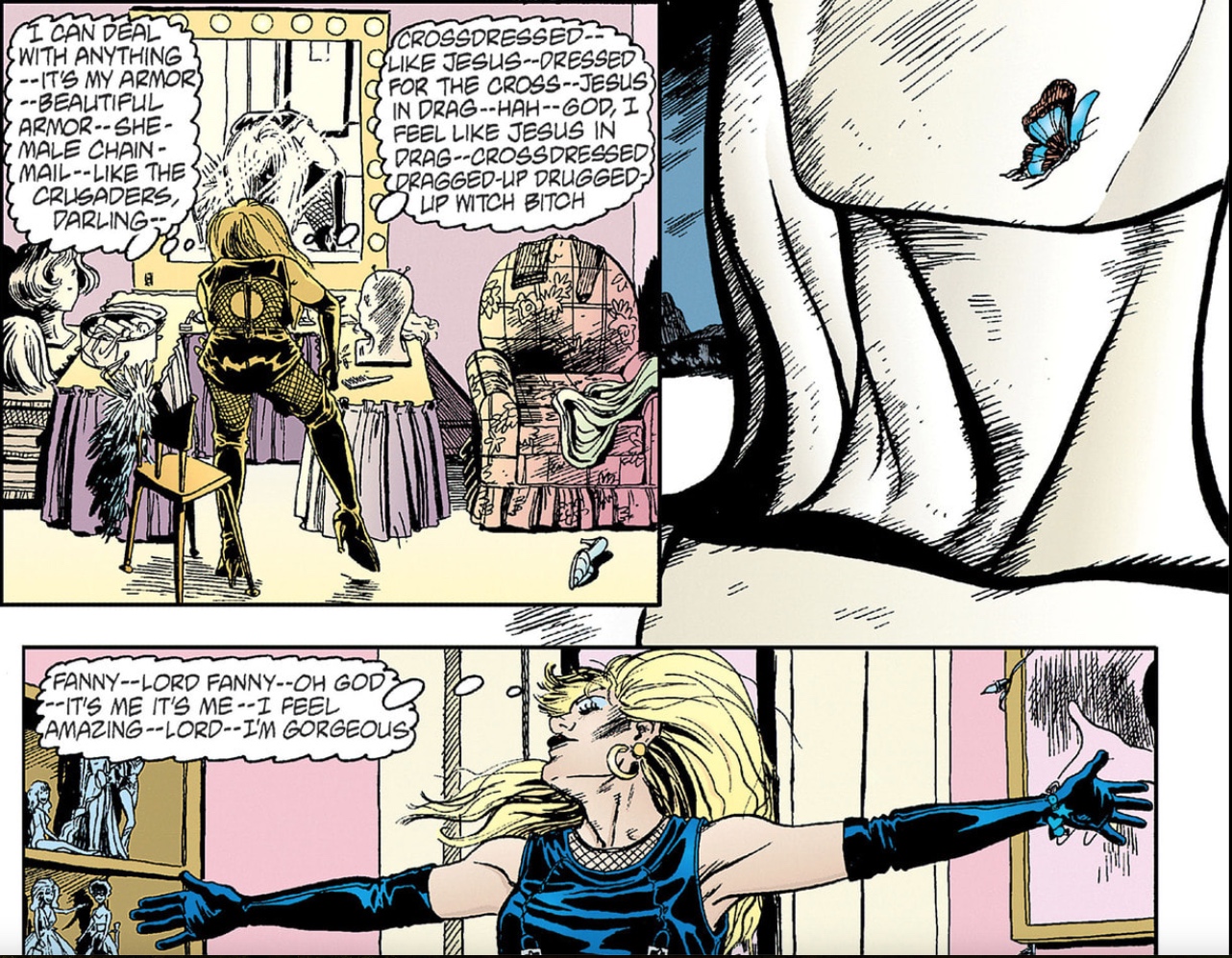

This is an image straight out of Phonogram, but it wasn't that book that came to mind. Instead, it was an older work featuring a mirror, from 1995, that I read sometime in the mid-2000s. Lord Fanny, in Grant Morrison's The Invisibles, preparing for the evening.

Fanny is -- tricky -- in the modern context. She appears to be a white British author's speculation on what a travesti shamen/witch might be like in a world where cause-and-effect magic is real and every conspiracy theory is true. Some of the worst neotribal excesses the '90s had to offer.

In practice, like most of the main cast, Fanny ends up being a chance for Grant Morrison to explore one aspect of their personality and gender, and the character ends up becoming an extremely elevated version of an anglophile transvestite circa 1995. The dual roles, the femme persona tapping into some inner self, both being part of a whole, etc.

For me, reading these books in the early/mid-2000s, believing that I wasn't one of the rare few true transexuals, Fanny offered me a model that was far more compelling than Harry LeSabre's closeted life. Ensconce myself with a group of bohemians and goths. Become a louder-than-life character -- an ontological gender terrorist. There are ways that worked for me and ways it didn't. By 2014 it had stopped working entirely -- the last time I presented femme was that spring before some new roommates moved in.

I remember this introduction to Laura Wilson resonating -- her doning her costume reminding me of those moments in front of the mirror when I'd snap my wig into place and get that rush of what we now call gender euphoria. I also remember the almost beat hitting me with a wave of sadness. Even then some part of me knew I was leaving something unfinished.

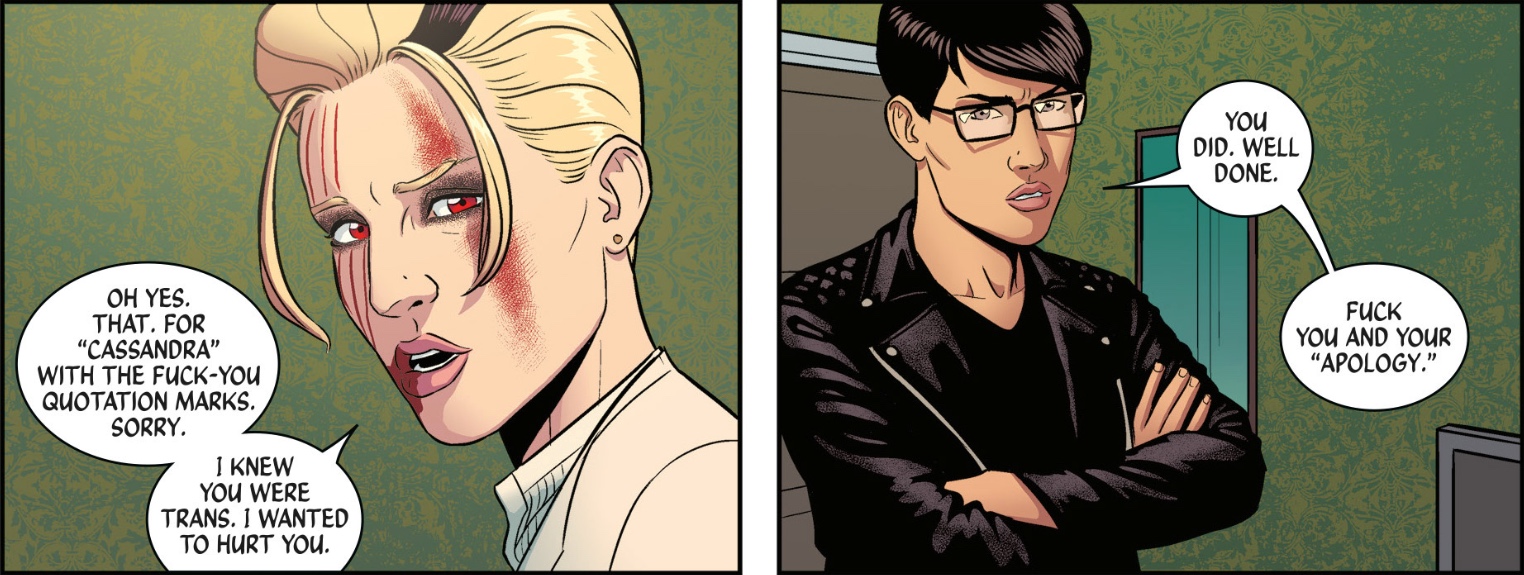

Cassandra

Cassandra Igarashi landed differently for me in this read. I'd remembered the character but had low-key forgotten she was a trans woman. This was not out of any deep repression, but more about how gay, queer, and trans characters were depicted in mainstream aspiring work in the 2010s.

Here's a quote from author Kieron Gillean near the end of the book's run. "It was just there"

DH: One of WicDiv's biggest strengths has been its normalization of diversity. A lot of writers would have called attention to that sort of thing, tooting their own horn for being so "woke", but you just did it and didn't make that big a deal about it. If someone was trans, they were trans. If they were gay, they were gay. It was just who they are, not something that was a main character trait, where it came before who they are as people. How important do you think that approach was to the success of the comic? How much do you think that approach to diversity and character informed the story?

KG: This is a complicated and large issue. We tried hard to not actually make an explicit selling point of the book. It was just there, because it's set in London and we wanted the book to feel like the city we love. WicDiv is no more diverse than London. We get uncomfortable with people offering us the proverbial cookies for it, while simultaneously how important it is to people to see characters like that in fiction.

The philosophy was that while a character's identity impacts their processing of the world and how the world treated them, we tried hard to not write stories primarily about someone's identity per se. There's a few areas I think we did, but they were very small. While (for example) Cass' identity as a trans woman certainly impacted how she approached things like the changing identity of becoming a god (she keeps her "Cassandra" even when Urdr, as clearly she'd already done a lot of work on deciding her identity, etc) her stories were about everything else in her - the messy specifics which made Cass, Cass.

This was not an uncommon way for gay, queer, and trans people to be depicted in mainstream aspiring media at the time, and it was in alignment with the politics of the era.

In late 2003 the Massachusetts Supreme Court ruled that the state's ban on same-sex marriage was unconstitutional. In 2004 the city of San Francisco started issuing marriage licenses to same-sex couples. This was a Big Deal and lasted about a month before the California Supreme Court ordered the city to stop (at the behest of the California attorney general). Later that year Massachusetts would begin issuing marriage licenses.

"Gay Marriage" became the focal point for LGBT politics in the US. The mainstream advocacy organization narrative that gay relationships were no different than straight ones became the dominant narrative. In the US individual states began issuing rulings and laws either legalizing gay marriage or aligning the state with the 1996 federal ban on gay marriage (the so-called defense of marriage act). On June 26th, 2015 the US Supreme Court issued a ruling that struck down the bans and forced every state to issue marriage licenses to same-sex couples who wanted them.

Cassandra materialized from the fictional ether near the height of this wave of gay respectability politics -- and her depiction reflects that. An attempt to wedge trans women into the same model. She's trans -- but that transness mostly goes unmentioned -- not out of any shame or malice, but out of a progressive ideal that "this shouldn't be a big deal, so let's not make it one". She's the same as anyone else.

That's the story anyway, and I think it's partially true. But there are other forces in play with any decision to deemphasize a character's queerness. To quote a late bit of fourth wall breaking in the book

All those books of destiny, those stories, telling you the way it's going to be. They just conceal the truth beneath it all. Look past the words. Remember they were written. Remember they're a writer's design, not yours.

There's a default position that big publishing companies take around pushing for work that appeals to as broad an audience as possible. More audience means more sales, or in the olden days, more people looking at the print advertising. Even if a creator can look past this, and see the ways that a non-mainstream book can find its audience and do well, they still need to contend with a system of editors, publishers, and store owners who might not agree with them.

The other pressure on depictions of queerness in media is the author's own identity, what they do, or don't want to share, and what they do, or don't want to be discussed if they've reached that particular level of "famous to niche communities but not famous enough to have fuck-off money". I remember WicDiv being a popular discussion point on Tumblr (or at least popular enough that Tumblr discussions leaked into the social media platforms I was on) in a way that felt like a balancing act of artistic intent vs. audience expectations.

Which, in a roundabout way, leads back to my initial impressions of Cassandra back in 2014. Trans, yes, but not in a way that felt particularly resonant or uncomfortably revealing. She felt more like a 40-year-old trying to contend with and depict an extremely online Tumblr user in their mid-20s with a strong autistic (complimentary) interest in social justice issues. Her status as "trans woman" felt incidental, but her "you're not wrong Walter you're just an asshole" energy hit pretty close to home.

Ten years later -- her status as a trans woman still feels incidental, in ways that weaken the character a bit. How did Cassandra come to transition pre-2014? How long has she been out? On HRT? Who, if anyone, is her community? Why is an extremely online Tumblr user in her mid-20s with a strong enough interest in social justice issues that she goes to war with the white girl playing a sun god mum when it comes to issues of gender or sexuality?

Cassandra is, in many ways, a better character than what we usually saw of trans women up until that point -- but also seems like squandered potential.

(FWIW -- Gillean's next series, Die, features a more explicitly trans feminine (perhaps a trans woman) character, Ash. I had thoughts on Ash several months after starting my own transition. She scans far more true to me, and this is almost certainly due to consults from the original social justice warrior.

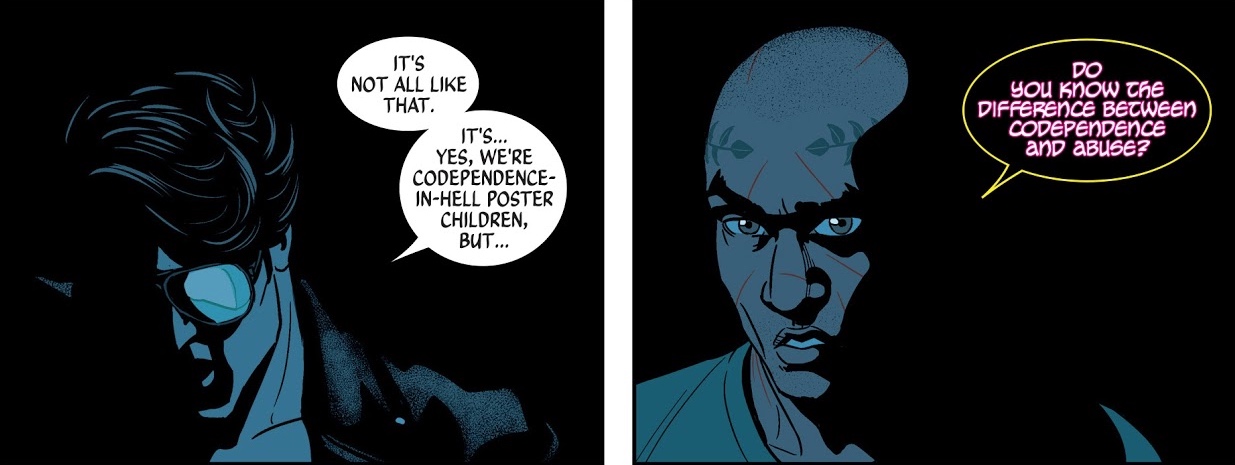

The Morrigan and Bahopment

Probably the most difficult of all the plot arcs to revisit was The Morrigan and Bahopment. Marian and Cameron. When I was rooting for someone in the Wicked + Divine it was almost always the goths. The Morrigan -- at least her exterior presentation -- was always the sort of goth lady I aspired to be. I hooked onto her character quickly.

Bahopment was specifically who I did not want to be or be around -- all machismo and swagger -- a little boy in Andrew Eldritch cosplay performing masculinity.

As the series progressed Gillean started making the implicit codependence of these doomed lovers explicit, as well as deepening that codependence into an abusive dynamic, with Marian the abuser and Cameron the abused.

...

...

Reading it in its day, I meow meow meowed over these story beats. I was still reading regularly but I had felt increasingly disconnected from a book that felt like it was made for a youth culture that wasn't mine. The beat felt forced, like a gimmick meant for someone else.

I remember reading Gillean's author notes for this issue six years earlier

And back to Marian, the heroine of her gothic novel, confronted with undeniable evidence that she’s a murdering monster who absolutely was driven by her own selfish desires. She denies it anyway, finding a way to persuade herself it’s not true.

No, she’s the hero. She’s going to bring Baphomet back at the cost of her own life. That must prove she’s the good person, right?

Morrigan is continuing her abuse the only way she can, while preserving her all-important idea that she was the good person.

So, of the three stories I mention, the one which climaxes is Morrigan’s solo plot. She rode her own story off the edge of a cliff rather than face the reality of what she has done. The other two, and the other ones, carry on, especially Baph and Morri’s relationship. Baph has to live with this.

When I was first explaining this to C, it had the desired effect. I then talked about my actual concern with it – that Marian’s too convincing. Some people will take it as a “She loved him really” beat, and could then be taken as Abusers Love Their Victims Really. C got it, but noted, it’s just too good to not do. I agree. I think it’s one of the best scenes in WicDiv, and I had to hit it as hard as we could, and then go on to deal with the aftermath of it.

When I read this in-era I remember being slightly taken aback. My initial read had been one of Marian realizing her fuckups and making amends for them the only way she knew how -- perhaps not exactly "she loved him really", but the actual abuse dynamic slid right off some protective barriers I had in place.

Reading it now -- there's a quote in Imogen Binnie's Nevada that I think of a lot.

... you can’t be one of the people in a relationship if you’re busily refusing to be a person.

The thing about busily refusing to be a person is it makes you attractive to a certain sort of controlling partner or spouse. If you're lucky enough to live in a city with a significant number of transitioning women or move in similar circles online, and you get to know these women during their transition, you'll notice a pattern where a lot of us eventually say some version of the phrase "I never thought that could happen to me".

Reading this now was an uncomfortable reminder of who I tried to be in the mid-to-late teens of the 21st century and what I settled for -- made double so by the fate of both Marian and Cameron.

Paths Taken

I don't dissociate through fiction like I used to. I still read and still enjoy resonating with characters, but I don't try to be them. I'm no longer trying on fiction suits for size. I'm glad to have revisited this series but it's left me with complicated feelings about my forties. A good chunk of my early transition has been spent finding ways to forgive myself for not transitioning earlier -- and I've mostly done that by realizing how much I was trying to be trans in a world that didn't have models for me.

The choices I made in my forties though -- I suppose it's one thing to have forgiven yourself for things you didn't do but an entirely different thing to forgive yourself for what it is you chose to do instead.