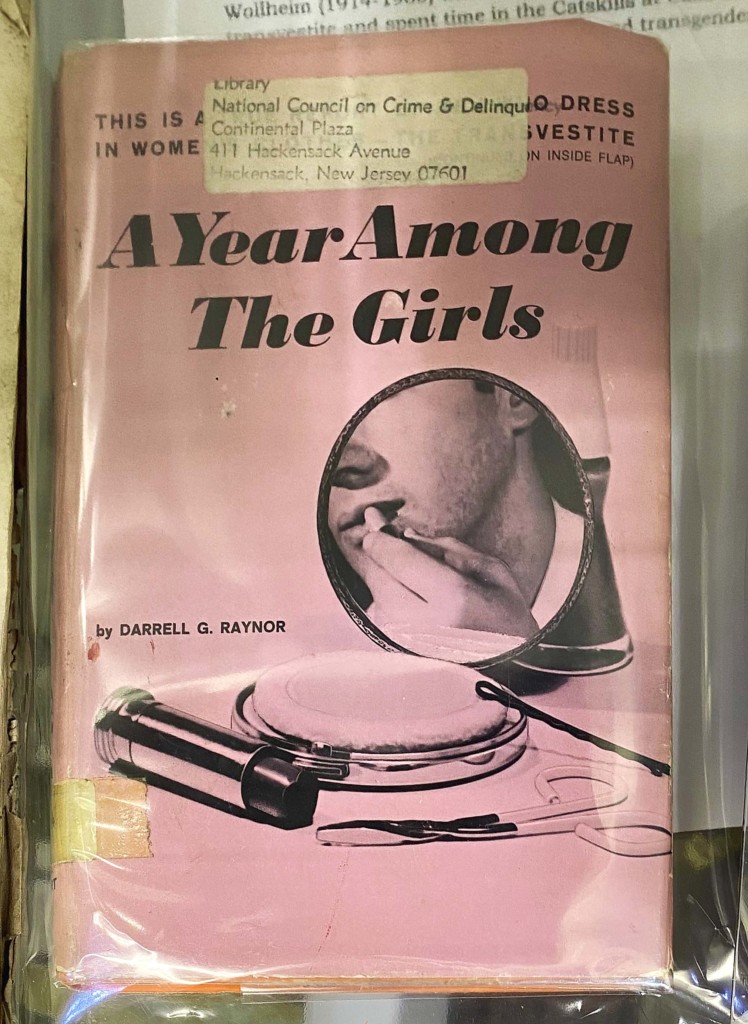

When I was hyper-focusing on Casa Susanna last summer, I kept coming across references to a book titled A Year Among The Girls by Darrell G. Raynor. Published in 1966, it's an account of one man's struggle to accept his cross-dressing and the year (1962) he spent establishing himself in both the New York City "transvestite scene", as well as with the nascent national organizing being done by Virginia Prince via her Transvestia magazine.

One interlibrary loan later, I finally got a chance to read this account of the mid-century cross-dressers who set a template for what it meant to be a certain sort of trans in America for the next few generations.

Light content warnings -- I've tried to use the pronouns people seemed to prefer towards the end of their lives. I'll also be quoting passages that refer to cross-dressers strictly as he, and I'll be using the word transvestite as that was the word en vogue in their own time, twenty years before Blanchard's redefinition.

The Year

The book's credited author is Darrell G. Raynor -- a pen name used by science fiction luminary Donald A. Wollheim. He starts the book with a cloak and dagger retelling of his first nervous meeting with Virginia Prince at her home in the hills of Los Angeles. After a brief recap of his near nervous breakdown over his cross-dressing and discovery of Prince's Transvestia magazine, the rest of the book recounts Wollheim meeting and corresponding with other cross-dressers who were part of the small but growing national network that centered around Prince's magazine.

Wollheim shares his observations about each individual cross-dresser's philosophy as he recounts his own experience with the practice and, as we might say in the 21st century, ponders his gender shit. In addition to his traveling around the country, he makes connections with a local community of cross-dressers centered around Susanna Valenti who, along with Marie Tonell (her wife), ran two different resorts for cross-dressers in the Catskill mountains in the late 1950s and 1960s.

The book culminates with a trip to the first of these resorts, the Chevalier D'Eon, in 1962 for a large Halloween party with, by Wollheim's count, seventy-one cross-dressers in attendance -- "no bunch of creampuffs or weak sisters." among them.

In closing Wollheim asserts that his involvement with this culture has eased the anxiety he felt around his own cross-dressing, and imagines what this might mean for others in his predicament.

The Girls

There are ways the experiences he describes are intimately familiar. The revelation of finding other trans people and realizing you're not alone, or how easy it was to fall into deep conversation with the others he met. Or the frustration with doctors and psychiatrists who write about trans people and know nothing of our lives.

Despite these moments of familiarity, Wollheim's perspective is a frustrating one for a trans reader in 2024. Throughout the book he can't let go of the idea that his situation is a detriment to his masculinity and that this detriment to his masculinity might make him, and by implication the others, unworthy humans or citizens. Whenever he introduces a new member of his network he emphasizes the deep masculinity of these transvestites when they're not, as we used to say, en femme -- even if they don't care to see themselves that way.

Worse still is both Wollheim's and Prince's heavy homophobia. Great pains are made to separate the cross-dressing done by transvestites of their social spheres from the so-called street queens of the era. This attitude is on display during his first meeting with Virginia Prince --

What of the homosexual queens? He scoffed. They are not of us. They are confused with us by the public, and they give us a bad name, but their drive is totally different from our drive. They are not interested in passing as women, or being associated with women. They are only interested in advertising their bodies to other men by the crude techniques of wearing women’s clothes, but always in such a way as to exaggerate, to carry on, to reveal that they are only mock women, men in skirts, flaunting themselves to show their real sex and their real intentions. These queens conduct themselves as harlots, but transvestites identify with ladies and carry themselves with propriety.

or in his own words

Once again, I repeat that tvs do not regard the mass appearances of men in female garb at "drag" balls or other such homosexual spectacles as having anything to do with them or their world. The two types of cross-dressers are and remain at opposite poles. They have no use for each other and they do not understand each other.

World War II and the Cold War loom heavily over the book, published twenty years after the formal end of hostilities. I haven't found any mention of Wollheim's war record -- whether he served or how, but born in 1914 he would have been twenty-eight when America entered the war -- and then thirty-five at the start of the Korean War and the McCarthyism of the 1950s. His young adulthood would have been awash in the propaganda of the era.

Wollheim goes out of his way to praise the war records of the cross-dressers he meets -- again creating an image of the all-American man who just happens to have a strange, quiet hobby. He praises the transvestites with engineering jobs who work in the defense industry, and there's a passage at the end of the Halloween Party that's revealing of the story Wollheim wanted to tell about his imagined fraternity.

I had come to know something about most of the men who were there. I recall sitting there watching the crowd of pseudo-women having fun and thinking to myself that this was no bunch of creampuffs or weak sisters.

There were sufficient ex-Navy men and retired flag officers there to crew and command a small war vessel.

There were enough trained aviation and Air Force personnel to put a medium bomber into the air and fly it anywhere on an action mission.

There were enough veterans, reserve soldiery, and Marines there to take an enemy machine-gun nest.

There was a commissioner of police from a medium sized New England city and enough men with peace-officer standing and training to police a township.

There were enough first-class engineers, designers, inventors, and managerial executives there to run a small high-technology plant.

In 1966 the United States was in the middle of its escalation of the war in Vietnam and would spend the next seven years funneling guns, bombs, and bodies into the conflict.

Wollheim's Cold War thinking reaches a crescendo as he theorizes that it is, perhaps, the atomic bomb itself and its capacity for relentless destruction that's led to more men embracing and expressing their feminine side.

I think the stresses of our society, hanging as it has been since 1945 on the brink of some sort of atomic abyss, are creating more and more tensions among mankind. I believe that the need to escape from reality is growing, that such terrible tensions require safety valves, and that one of the most successful escape mechanisms is total disguise. Dress like a woman, pretend to be a woman, change your name and you have for a few minutes or a few hours expunged your guilt of being part of a society rotten to the core and heading for disaster.

One Against the Moon

As the book ends Wollheim describes his falling out with Virginia Prince over the politics of her local "Hose and Heels" club and his decision not to involve himself in a social purge of members Prince disagreed with.

On the secret level, there is the idea of a fraternal order, open only to the initiate, with its own rules and closed meetings. Such an organization has already been attempted, but it has not gained the support of the great majority of tvs.

The organization was founded by Virginia and is run as a one-man operation by that magazine publisher. Unlike respectable fraternal orders, its membership is known only to its owner-directory, and members know each other only through that director’s coded file — — Most tvs regard it simple as a return to the locked room—and consider it as a commercial operation on Virginia’s part. Unfortunately the writer of this book must also so regard it.

Prince would go on to expand her Full Personality Expression clubs over the next few decades, eventually merging them with a separate schism group to form the Society for the Second Self, also known as Tri-Ess. At its height Tri-Ess had twenty-five chapters -- in 2025 the organization website lists three.

Wollheim would become managing editor and a contributor (under the name D. Rhodes) for the magazine Turnabout -- seen as a counterpoint to Prince's Transvestia. As a contributor, his interests were mostly focused on transvestite literature, a roundup of cross-dressing mentions in wider media, and occasional gossip and goings on in the New York City and national transvestite scene.

He also outlined a theory of transvestism that separates people into two camps -- overs and unders -- each with a distinct set of personality traits, tendencies, and backgrounds. This theory includes casting one of the groups as more prone to thinking of themselves as dual-gendered or women, wanting to have sex with men, and seeking out bottom surgery. A precursor to the evolutionary dead end of Blanchard's autogynephilia.

After this, his name and aliases mostly drop from the historic trans records I've found. Prince will mention him briefly in Issue #100 of Transvestia, published in 1979

Interestingly enough, I have received a large number of letters over the years from people who had first heard of me through the book. So, maybe I owe Raynor a vote of thanks after all. Incidentally, we are on good terms with each other by this point and I have visited him at his motel in Los Angeles and saw him in New York when I was there in the fall of '78.

Taking Up Space

Price and Wollheim both are frustrating figures for any trans woman looking to the past. Their wealth and position in the publishing industry allowed their ideas and understanding about themselves to play an outsized influence in the ways trans women and trans feminine folks thought about ourselves well into the 1970s, 1980s, and even 1990s. There are lessons to be learned from these leaders -- but mostly about what not to do.

If there's anyone from the period I look at with some warmth, it's Susanna Valenti. Wollheim praises Susanna's accomplishments as a broadcaster with a patriotic war record but is less impressed with the organizing Susanna did around the New York transvestite community.

Susanna is easy to talk to, intelligent, yet not inclined to domineer or be forceful. Meeting him solved one enigma for me-why it was that the New York world of transvestites was so loosely contained, never organized into any kind of formal clubs, and resistant to any such organizational attempts. It proved to me why, with Susanna the obvious and accepted center of society, nothing seemed to jell - as evidently it had in Los Angeles around the forceful, opinionated personality of Virginia.

Susanna was simply an easygoing type, not basically a leader and with no interest in becoming a leader.

Wollheim, I think, misses the mark here and confuses leadership with control. Susanna's low-key approach let her network flourish. Whether through the resorts or the gatherings she held in her New York City apartment she pulled together an eclectic bunch of people we'd now understand as transfeminine who were learning how to navigate the world.

As she was beginning to make her transness manifest in the real world she was also creating a place for others to do the same. Places to talk about themselves and, for some, to realize what it was they both needed and wanted. As famed trans woman Katherine Cummings put it in the 2022 Casa Susana documentary film

The rest of the weekend, a lot of people got into groups and said, "Why me? "Why am I like this?"

What was this thing, and why was it us, and how is it different from being gay and how is it different from -- well, in those days we thought we were just cross-dressers. So, how was that different from being a transgender person who really wanted to change?

Trans women, in rooms, taking up space. Talking to each other face to face. The thing, more than any other thing, that changes our lives for the better.